Why Amazon EC2/S3?

- Pretty good reliability. Datacenters go down too. Multitenancy adds some risk, but it’s not bad.

- Good reporting and support. They have really good architects and they know the problems

- Nice peripherals, especially when you are growing. You can spin up in App Engine and talk to their managed cache, load balancing, map reduce, managed databases, and all the other parts that you don’t have to write yourself. You can bootstrap on Amazon’s services and then evolve them when you have the engineers.

- New instances available in seconds. The power of the cloud. Especially with two engineers you don’t have to worry about capacity planning or wait two weeks to get your memcache. 10 memcaches can be added in a matter of minutes.

- Cons: limited choice. Until recently you could get SSDs and you can’t get large RAM configurations.

- Pros: limited choice. You don’t end up with a lot of boxes with different configurations.

Why MySQL?

- Really mature.

- Very solid. It’s never gone down for them and it’s never lost data.

- You can hire for it. A lot of engineers know MySQL.

- Response time to request rate increases linearly. Some technologies don’t respond as well when the request rate spikes.

- Very good software support – XtraBackup, Innotop, Maatkit

- Great community. Getting questions answered is easy.

- Very good support from companies like Percona.

- Free – important when you don’t have any funding initially.

Why Memcache?

- Very mature.

- Really simple. It’s a hashtable with a socket jammed in.

- Consistently good performance

- Well known and liked.

- Consistently good performance.

- Never crashes.

- Free

Why Redis?

- Not mature, but it’s really good and pretty simple.

- Provides a variety of data structures.

- Has persistence and replication, with selectability on how you want them implemented. If you want MySQL style persistence you can have it. If you want no persistence you can have it. Or if you want 3 hour persistence you can have it.

- Your home feed is on Redis and is saved every 3 hours. There’s no 3 hour replication. They just backup every 3 hours.

- If the box your data is stored on dies, then they just backup a few hours. It’s not perfectly reliable, but it is simpler. You don’t need complicated persistence and replication. It’s a lot simpler and cheaper architecture.

- Well known and liked.

- Consistently good performance.

- Few failure modes. Has a few subtle failure modes that you need to learn about. This is where maturity comes in. Just learn them and get past it.

- Free

Solr

- A great get up and go type product. Install it and a few minutes later you are indexing.

- Doesn’t scale past one box. (not so with latest release)

- Tried Elastic Search, but at their scale it had trouble with lots of tiny documents and lots of queries.

- Now using Websolr. But they have a search team and will roll their own.

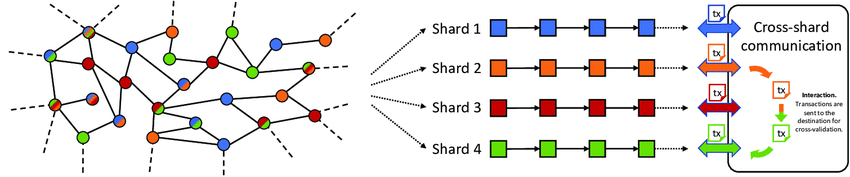

Clustering Vs Sharding

- During rapid growth they realized they were going to need to spread their data evenly to handle the ever increasing load.

- Defined a spectrum to talk about the problem and they came up with a range of options between Clustering and Sharding.

Clustering – Everything Is Automatic:

- Examples: Cassandra, MemBase, HBase

- Verdict: too scary, maybe in the future, but for now it’s too complicated and has way too many failure modes.

- Properties:

- Data distributed automatically

- Data can move

- Rebalance to distribute capacity

- Nodes communicate with each other. A lot of crosstalk, gossiping and negotiation.

- Pros:

- Automatically scale your datastore. That’s what the white papers say at least.

- Easy to setup.

- Spatially distribute and colocate your data. You can have datacenter in different regions and the database takes care of it.

- High availability

- Load balancing

- No single point of failure

- Cons (from first hand experience):

- Still fairly young.(the origin blog wrote from 2013, now is 2021)

- Fundamentally complicated. A whole bunch nodes have to symmetrical agreement, which is a hard problem to solve in production.

- Less community support. There’s a split in the community along different product lines so there’s less support in each camp.

- Fewer engineers with working knowledge. Probably most engineers have not used Cassandra.

- Difficult and scary upgrade mechanisms. Could be related to they all use an API and talk amongst themselves so you don’t want them to be confused. This leads to complicated upgrade paths.

- Cluster Management Algorithm is a SPOF. If there’s a bug it impacts every node. This took them down 4 times.

- Cluster Managers are complex code replicated over all nodes that have the following failure modes:

- Data rebalance breaks. Bring a new box and data starts replicating and then it gets stuck. What do you do? There aren’t tools to figure out what’s going on. There’s no community to help, so they were stuck. They reverted back to MySQL.

- Data corruption across all nodes. What if there’s a bug that sprays badness into the write log across all of them and compaction or some other mechanism stops? Your read latencies increase. All your data is screwed and the data is gone.

- Improper balancing that cannot be easily fixed. Very common. You have 10 nodes and you notice all the node is on one node. There’s a manual process, but it redistributes the load back to one node.

- Data authority failure. Clustering schemes are very smart. In one case they bring in a new secondary. At about 80% the secondary says it’s primary and the primary goes to secondary and you’ve lost 20% of the data. Losing 20% of the data is worse than losing all of it because you don’t know what you’ve lost.

Sharding – Everything Is Manual:

- Verdict: It’s the winner. Note, I think their sharding architecture has a lot in common with Flickr Architecture.

- Properties:

- Get rid of all the properties of clustering that you don’t like and you get sharding.

- Data distributed manually

- Data does not move. They don’t ever move data, though some people do, which puts them higher on the spectrum.

- Split data to distribute load.

- Nodes are not aware of each other. Some master node controls everything.

- Pros:

- Can split your database to add more capacity.

- Spatially distribute and collocate your data

- High availability

- Load balancing

- Algorithm for placing data is very simple. The main reason. Has a SPOF, but it’s half a page of code rather than a very complicated Cluster Manager. After the first day it will work or won’t work.

- ID generation is simplistic.

- Cons:

- Can’t perform most joins.

- Lost all transaction capabilities. A write to one database may fail when a write to another succeeds.

- Many constraints must be moved to the application layer.

- Schema changes require more planning.

- Reports require running queries on all shards and then perform all the aggregation yourself.

- Joins are performed in the application layer.

- Your application must be tolerant to all these issues.

When To Shard?

- If your project will have a few TBs of data then you should shard as soon as possible.

- When the Pin table went to a billion rows the indexes ran out of memory and they were swapping to disk.

- They picked the largest table and put it in its own database.

- Then they ran out of space on the single database.

- Then they had to shard.

Transition To Sharding

- Started the transition process with a feature freeze.

- Then they decided how they wanted to shard. Want to perform the least amount of queries and go to least number of databases to render a single page.

- Removed all MySQL joins. Since the tables could be loaded into separate partitions joins would not work.

- Added a ton of cache. Basically every query has to be cached.

- The steps looked like:

- 1 DB + Foreign Keys + Joins

- 1 DB + Denormalized + Cache

- 1 DB + Read Slaves + Cache

- Several functionally sharded DBs + Read slaves + Cache

- ID sharded DBs + Backup slaves + cache

- Earlier read slaves became a problem because of slave lag. A read would go to the slave and the master hadn’t replicated the record yet, so it looked like a record was missing. Getting around that require cache.

- They have background scripts that duplicate what the database used to do. Check for integrity constraints, references.

- User table is unsharded. They just use a big database and have a uniqueness constraint on user name and email. Inserting a User will fail if it isn’t unique. Then they do a lot of writes in their sharded database.

How To Shard?

- Looked at Cassandra’s ring model. Looked at Membase. And looked at Twitter’s Gizzard.

- Determined: the least data you move across your nodes the more stable your architecture.

- Cassandra has a data balancing and authority problems because the nodes weren’t sure of who owned which part of the data. They decided the application should decide where the data should go so there is never an issue.

- Projected their growth out for the next five years and presharded with that capacity plan in mind.

- Initially created a lot of virtual shards. 8 physical servers, each with 512 DBs. All the databases have all the tables.

- For high availability they always run in multi-master replication mode. Each master is assigned to a different availability zone. On failure the switch to the other master and bring in a new replacement node.

- When load increasing on a database:

- Look at code commits to see if a new feature, caching issue, or other problem occurred.

- If it’s just a load increase they split the database and tell the applications to find the data on a new host.

- Before splitting the database they start slaves for those masters. Then they swap application code with the new database assignments. In the few minutes during the transition writes are still write to old nodes and be replicated to the new nodes. Then the pipe is cut between the nodes.

ID Structure

- 64 bits:

- shard ID: 16 bits

- type : 10 bits – Pin, Board, User, or any other object type

- local ID – rest of the bits for the ID within the table. Uses MySQL auto increment.

- Twitter uses a mapping table to map IDs to a physical host. Which requires a lookup. Since Pinterest is on AWS and MySQL queries took about 3ms, they decided this extra level of indirection would not work. They build the location into the ID.

- New users are randomly distributed across shards.

- All data (pins, boards, etc) for a user is collocated on the same shard. Huge advantage. Rendering a user profile, for example, does not take multiple cross shard queries. It’s fast.

- Every board is collocated with the user so boards can be rendered from one database.

- Enough shards IDs for 65536 shards, but they only opened 4096 at first, they’ll expand horizontally. When the user database gets full they’ll open up more shards and allow new users to go to the new shards.

Lookups

- If they have 50 lookups, for example, they split the IDs and run all the queries in parallel so the latency is the longest wait.

- Every application has a configuration file that maps a shard range to a physical host.

- “sharddb001a”: : (1, 512)

- “sharddb001b”: : (513, 1024) – backup hot master

- If you want to look up a User whose ID falls into sharddb003a:

- Decompose the ID into its parts

- Perform the lookup in the shard map

- Connect to the shard, go to the database for the type, and use the local ID to find the right user and return the serialized data.

Objects And Mappings

- All data is either an object (pin, board, user, comment) or a mapping (user has boards, pins has likes).

- For objects a Local ID maps to a MySQL blob. The blob format started with JSON but is moving to serialized thrift.

- For mappings there’s a mapping table. You can ask for all the boards for a user. The IDs contain a timestamp so you can see the order of events.

- There’s a reverse mapping, many to many table, to answer queries of the type give me all the users who like this pin.

- Schema naming scheme is noun_verb_noun: user_likes_pins, pins_like_user.

- Queries are primary key or index lookups (no joins).

- Data doesn’t move across database as it does with clustering. Once a user lands on shard 20, for example, and all the user data is collocated, it will never move. The 64 bit ID has contains the shard ID so it can’t be moved. You can move the physical data to another database, but it’s still associated with the same shard.

- All tables exist on all shards. No special shards, not counting the huge user table that is used to detect user name conflicts.

- No schema changes required and a new index requires a new table.

- Since the value for a key is a blob, you can add fields without destroying the schema. There’s versioning on each blob so applications will detect the version number and change the record to the new format and write it back. All the data doesn’t need to change at once, it will be upgraded on reads.

- Huge win because altering a table takes a lock for hours or days. If you want a new index you just create a new table and start populating it. When you don’t want it anymore just drop it. (no mention of how these updates are transaction safe).

Rendering A User Profile Page

- Get the user name from the URL. Go to the single huge database to find the user ID.

- Take the user ID and split it into its component parts.

- Select the shard and go to that shard.

- SELECT body from users WHERE id = <local_user_id>

- SELECT board_id FROM user_has_boards WHERE user_id=<user_id>

- SELECT body FROM boards WHERE id IN (<boards_ids>)

- SELECT pin_id FROM board_has_pins WHERE board_id=<board_id>

- SELECT body FROM pins WHERE id IN (pin_ids)

- Most of the calls are served from cache (memcache or redis), so it’s not a lot of database queries in practice.

Scripting

- When moving to a sharded architecture you have two different infrastructures, one old, the unsharded system, and one new, the sharded system. Scripting is all the code to transfer the old stuff to the new stuff.

- They moved 500 million pins and 1.6 billion follower rows, etc

- Underestimated this portion of the project. They thought it would take 2 months to put data in the shards, it actually took 4-5 months. And remember, this was during a feature freeze.

- Applications must always write to both old and new infrastructures.

- Once confident that all your data is in the new infrastructure then point your reads to the new infrastructure and slowly increase the load and test your backends.

- Built a scripting farm. Spin up more workers to complete the task faster. They would do tasks like move these tables over to the new infrastructure.

- Hacked up a copy of Pyres, a Python interface to Github’s Resque queue, a queue on built on top of redis. Supports priorities and retries. It was so good they replaced Celery and RabbitMQ with Pyres.

- A lot of mistakes in the process. Users found errors like missing boards. Had to run the process several times to make sure no transitory errors prevented data from being moved correctly.

Development

- Initially tried to give developers a slice of the system. Each having their own MySQL server, etc, but things changed so fast this didn’t work.

- Went to Facebook’s model where everyone has access to everything. So you have to be really careful.

Future Directions

- Service based architecture.

- As they are starting to see a lot of database load they start to spawn a lot of app servers and a bunch of other servers. All these servers connect to MySQL and memcache. This means there are 30K connections on memcache which takes up a couple of gig of RAM and causes the memcache daemons to swap.

- As a fix these are moving to a service architecture. There’s a follower service, for example, that will only answer follower queries. This isolates the number of machines to 30 that access the database and cache, thus reducing the number of connections.

- Helps isolate functionality. Helps organize teams around around services and support for those services. Helps with security as developer can’t access other services.

Lessons Learned

- It will fail. Keep it simple.

- Keep it fun. There’s a lot of new people joining the team. If you just give them a huge complex system it won’t be fun. Keeping the architecture simple has been a big win. New engineers have been contributing code from week one.

- When you push something to the limit all these technologies fail in their own special way.

- Architecture is doing the right thing when growth can be handled by adding more of the same stuff. You want to be able to scale by throwing money at the problem by throwing more boxes at the problem as you need them. If your architecture can do that, then you’re golden.

- Cluster Management Algorithm is a SPOF. If there’s a bug it impacts every node. This took them down 4 times.

- To handle rapid growth you need to spread data out evenly to handle the ever increasing load.

- The least data you move across your nodes the more stable your architecture. This is why they went with sharding over clusters.

- A service oriented architecture rules. It isolates functionality, helps reduce connections, organize teams, organize support, and improves security.

- Asked yourself what your really want to be. Drop technologies that match that vision, even if you have to rearchitecture everything.

- Don’t freak out about losing a little data. They keep user data in memory and write it out periodically. A loss means only a few hours of data are lost, but the resulting system is much simpler and more robust, and that’s what matters.

NOTE: save for me!